Imagine a small device so efficient that it could clear drinking water of pathogens instantly using a small, solid-state ultraviolet (UV) LED powered by just 12 volts.

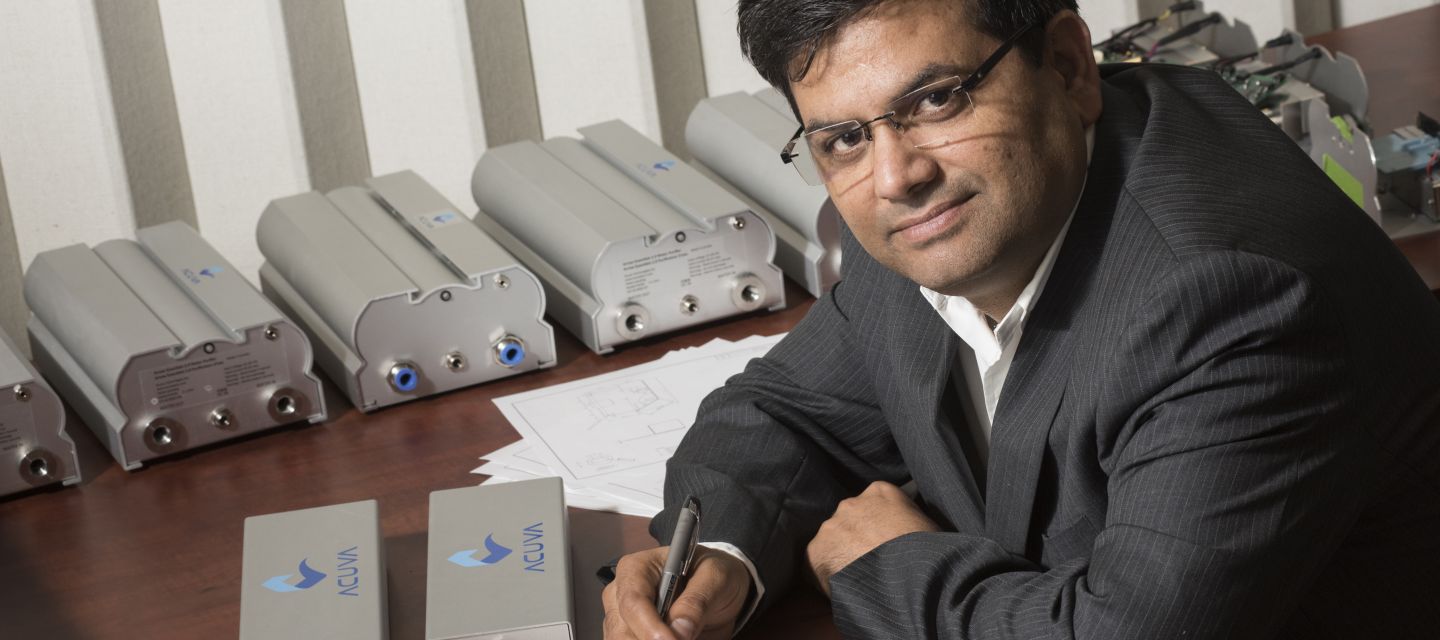

Manoj Singh isn’t just imagining such a device — as CEO of Acuva, he’s manufacturing them by leveraging technology developed at UBC.

Singh earned an MBA in strategic management at UBC in 2010. He took on corporate assignments in both India and Canada, but was soon bitten by the entrepreneurship bug. In 2013, he reached out to UBC’s University-Industry Liaison Office (UILO). The office helps forge partnerships for the university by linking breakthrough research and technology with industry, entrepreneurs, government and non-profit organizations through licensing agreements.

“I reviewed many technologies, but liked the commercial possibilities of the water-purification technology and was impressed by its potential social impact,” says Singh. “I could see myself making a positive impact on millions of people’s lives. UBC also wanted to know that I was the person who could take this technology to its fullest commercial potential.”

His confidence in the potential of the technology grew further after meeting with Dr. Fariborz Taghipour, a professor at UBC’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, who developed the technology. Acuva was born soon after in 2014.

UV light is already one of the most effective methods of removing pathogens from water. Its downside? The current state of the technology is not easily scaled down for household use. UV lamps are expensive and create a negative environmental impact following disposal. UV treatment plants require enormous energy to operate and the lamps must remain on throughout the entire treatment cycle. The larger treatment plants also require significant maintenance, in part to remove mineral scale from the UV lamps.

The genius behind Acuva is the use of much more efficient UV LEDs, which require far less energy and little maintenance to provide the same water-purification benefits.

“With technological improvements, UV radiation produced by the LEDs is becoming much more powerful for the purposes of disinfection,” says Singh. “If you installed an Acuva purifier under a sink, you could open the faucet and purify water in real time with regular flow as it passes through the pipes. The unit only needs to be turned on when you want drinking water.”

Acuva is currently focusing on early adopters in markets identified by UBC experts: boat owners, recreational-vehicle owners and cottagers in North America.

“These are flow-through units that need to be connected to a water supply,” says Singh. “If you were boating on a fresh-water lake, you could make clean, safe and palatable drinking water from the lake with the Acuva unit.”

The price of the product is already dropping. Units are selling for as little as 30 per cent of the price offered last year.

“We’re expecting tremendous price reductions over the near term,” says Singh. “The journey through early markets has taken us from concept to product and significant improvements in economy of scale. We hope to see this phase attracting global industry partners.”

Next stop: emerging markets such as households in India that already use expensive devices to purify water supplied by utilities. “Where grid electricity is unreliable, the units need only be turned on when water is needed,” Singh explains.

Singh envisions further economies of scale soon, making lower-cost units available in remote communities. These could even be powered by small photovoltaic cells in off-grid locations.

While the technology drove the company, UBC was essential to its success, says Singh. He consulted with a team of six entrepreneurs in residence who provided hands-on business coaching. Singh also had access to a UBC network of more than 130 industry mentors who help companies like his take ideas through value proposition and into the marketplace.

Acuva was offered two offices on the UBC campus, one for testing and assembly of products and the other a management office. The company currently employs 13 people. Two thirds of them have associations with UBC.

“Acuva is a great example of a company that took advantage of everything UBC offers to assist new ventures. Over the past 10 years, we’ve really seen a shift, where more of our faculty, students and staff are thinking about taking scientific and technological breakthroughs to a point where they make an impact on the world.”

Gail Murphy, UBC’s Vice-president, Research and Innovation.

Decades ago, UBC was one of the first universities to establish a UILO. She notes that UBC’s Lean Launch Pad Accelerator Programs have also assisted in the development of 136 ventures over the past three years.

“It’s really important for UBC to provide the support mechanisms to help entrepreneurs in new ventures,” she says.

Singh notes that Acuva isn’t simply a one-trick pony.

“We’re not just a water-purification company,” he says. “We’re a UBC-inspired technology company that knows how to kill pathogens. We’ll continue to partner with UBC to develop new markets for this technology to clean water, air and even medical devices.”

Acuva CEO, Manoj Singh