More than 100,000 people live in Canada’s North, a beautiful, cold place home to many of the country’s First Peoples. It’s also a place where the cost of food can be as harsh as the climate.

In the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, the cold makes it difficult to grow food locally. Some remote communities have no roads and food is flown in. In 2015, the federal government announced it would spend an additional $40 million over four years on Nutrition North, a $60 million annual food subsidy program.

When a head of cabbage can cost upwards of $28, many northerners simply go hungry, skip meals, or survive on diets of mostly processed foods. But a team from the University of British Columbia believes they can help change that.

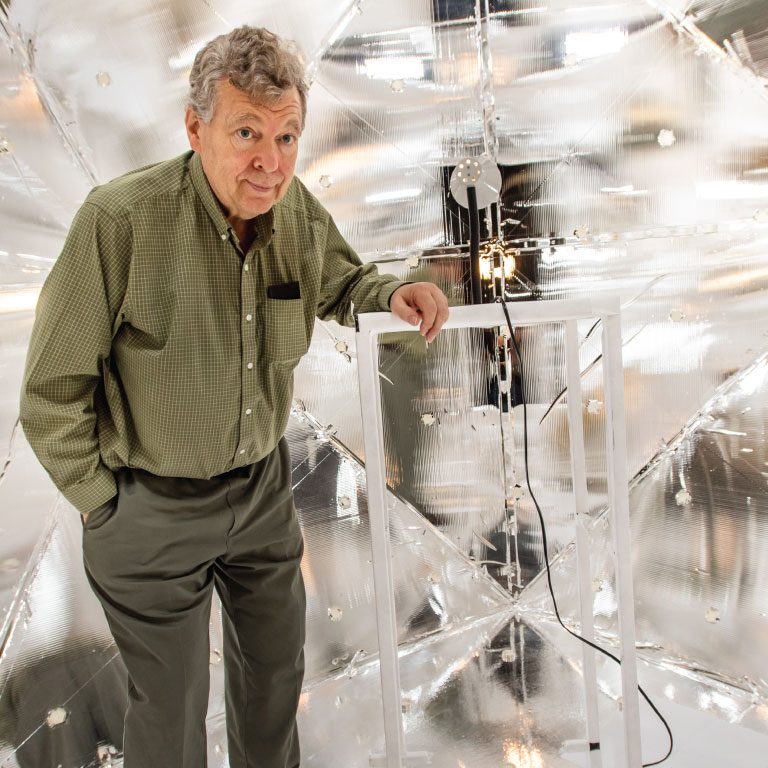

UBC physicist and engineer Lorne Whitehead is working on a new insulation system for greenhouses, called Geoleaf, with a team that includes research associate Michele Mossman, graduate and undergraduate students.

“This would drastically alter the food production capabilities of a greenhouse,” said Whitehead, who holds over a hundred patents in applied physics and was initially spurred to look at greenhouse lighting after repeated requests from industry.

Geoleaf uses panels of Mylar®, an inexpensive polyester film material, fastened together to resemble honeycomb blinds. The panels can expand like an accordion or compress using electrostatic current with the flick of a switch. This variable insulation is the critical feature greenhouses lack to thrive in extreme climates, cold or tropical.

During daylight hours, the panels are compressed to allow light in. When light fades, the panels expand, allowing the ceiling to act as a highly thermal insulator, trapping the heat inside. They can be installed or retrofitted onto a greenhouse’s glass ceiling.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/EBgHfVfwpUM.jpg?itok=HUoSNUJv","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=EBgHfVfwpUM","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

There have been many attempts to improve food security in the North, from growing food in greenhouses, domes, and igloos, to hydroponics, a system of growing food without soil, or to vertical farming, growing food in stacked layers.

These approaches all consume too much energy or are too expensive with the cost of electricity to become widespread. Importing produce ends up being cheaper and easier. While not the first to use variable insulation, Geoleaf’s inexpensive materials and sustainable power source makes it more energy efficient and cost effective than other alternatives.

It’s a system that’s been seven years in the making. Since 2009, the UBC team has worked on different iterations to variable insulation, but hit a number of stumbling blocks along the way. Earlier versions were too expensive, too difficult to maintain or too labour intensive to commercialize.

“Our first, second, third attempts all failed,” said Whitehead. “The likelihood of getting to what I call the truly innovative forefront is higher if you can be persistent. It does take patience.”

But trial and error has never daunted Whitehead, who sees errors as opportunities.

“I often tell my students that any idea is unlikely to be truly new. Others will have thought of it, tried, and failed because they hit a problem and they gave up. I always figured the faster you can discover that problem the better. As you keep moving forward, your competition goes down significantly.”

After a year spent at a greenhouse in Langley, B.C., working out some of the remaining design kinks, the UBC team believes the current version of Geoleaf is ready to be fully tested.

Professor Lorne Whitehead: I often tell my students that any idea is unlikely to be truly new. Others will have thought of it, tried, and failed because they hit a problem and they gave up. I always figured the faster you can discover that problem the better. As you keep moving forward, your competition goes down significantly.

To fund the work, Whitehead has applied for a strategic grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and is currently looking to procure additional funds to develop the prototype further.

“We are keenly aware that food security in the North isn’t simply a technology problem,” said Mossman. “There are social, cultural, economic and political factors that all need to be aligned in order to properly address food security. As scientists, we are one piece of the puzzle with the tech side.”

This winter, the UBC team will take their prototype to Whitehorse. There, they will work with the local community and the Cold Climate Innovation Centre at Yukon College to test the full-scale Geoleaf system in a working greenhouse.

For Whitehead, Geoleaf feels like a necessity.

“I believe the experts who say the future of food production is in structures,” he said. “We need to grow food closer to where people live.”

In the long winters of Canada‘s North, it could be an innovation that germinates a bright head of green lettuce or homegrown cabbage, taking the costly price tag off what many in Canada take for granted on their dinner tables every night.