Every day, researchers across a variety of disciplines—from medicine to sociology, mathematics, nursing and engineering—are conducting research to gain a deeper understanding of the factors driving the overdose crisis in BC and to determine potential solutions.

M-J Milloy sees firsthand the impact of the overdose crisis in British Columbia.

As a professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and research scientist at the BC Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU), Milloy works directly with people who use drugs. He and his family also live in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, a neighbourhood known for high levels of drug use, poverty, crime, mental health challenges and homelessness.

“The overdose crisis is something that my family and I see every day,” he said. “We’ve lost research participants to the crisis. I’ve met parents who have lost their children. As the father of an eight-year-old daughter who means everything to me, I just can’t fathom it. It’s a heavy responsibility, but it’s why we do this work—no one should ever have to lose someone as a result of something that is preventable.”

In B.C., unintended death due to illicit drug overdose is the leading cause of preventable death. While the Downtown Eastside is deep in the grips of the overdose crisis, the issue is also devastating communities across the country and affecting people from all walks of life. The number of overdose deaths in this province increased from 211 in 2010 to 1,535 in 2018. In 2016, the rapid and alarming rise of illicit drug-related overdoses and deaths prompted then Provincial Health Officer Dr. Perry Kendall to declare a state of emergency which remains in effect to this day. Fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances—powerful synthetic opioids similar to morphine but 50 to 100-times more potent—continue to be a significant driver behind the crisis.

UBC’s role in tackling the crisis

In April 2018, UBC and BCCSU brought together researchers, community members and people who use drugs for a roundtable discussion to explore issues of stigma related to substance use and addiction. That discussion has helped inform the university’s response to the overdose crisis through its research, teaching and community engagement.

“When it comes to the overdose crisis, we need all partners on board to continue saving lives and help people find the treatment and recovery services that will work for them long term,” said Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Judy Darcy. “UBC’s dedication to helping address this crisis is vital to our overall work and aligns with our focus to take actions based on evidence with input from experts and people with lived experience.”

“UBC’s dedication to helping address this crisis is vital to our overall work and aligns with our focus to take actions based on evidence with input from experts and people with lived experience.”

For Milloy, whose research is focused on examining the potential of cannabis in addressing the overdose crisis and other substance use disorders, the support of the university and provincial government—as well as feedback from community members who are helped by his research—keeps him motivated in his work.

“It’s been great to see a lot of people at the university, from President Santa Ono and down, saying that we’ve got to contribute to this and try to beat back this crisis,” he said. “This is the defining crisis of our age and—not to be too biblical about things—but we will be judged by the actions that we took during the crisis, as we should be.”

Milloy is just one of dozens of scientists at UBC working to address the problem. Every day, researchers across a variety of disciplines—from medicine to sociology, mathematics, nursing and engineering—are conducting research to gain a deeper understanding of the factors driving the crisis and to determine potential solutions.

Reducing stigma saves lives

Dr. Jane Buxton, professor in the UBC school of population and public health and harm reduction lead at the BC Centre for Disease Control, believes part of the solution lies in ensuring that the voices of people who use drugs are heard when developing policies to reduce substance-related harms.

Making sure that we listen is vital because people who use drugs know what’s going on,” said Buxton. “They are the experts in the reality of drug use—their lived experience means they can identify the needs of their community and what is acceptable to people who use drugs.”

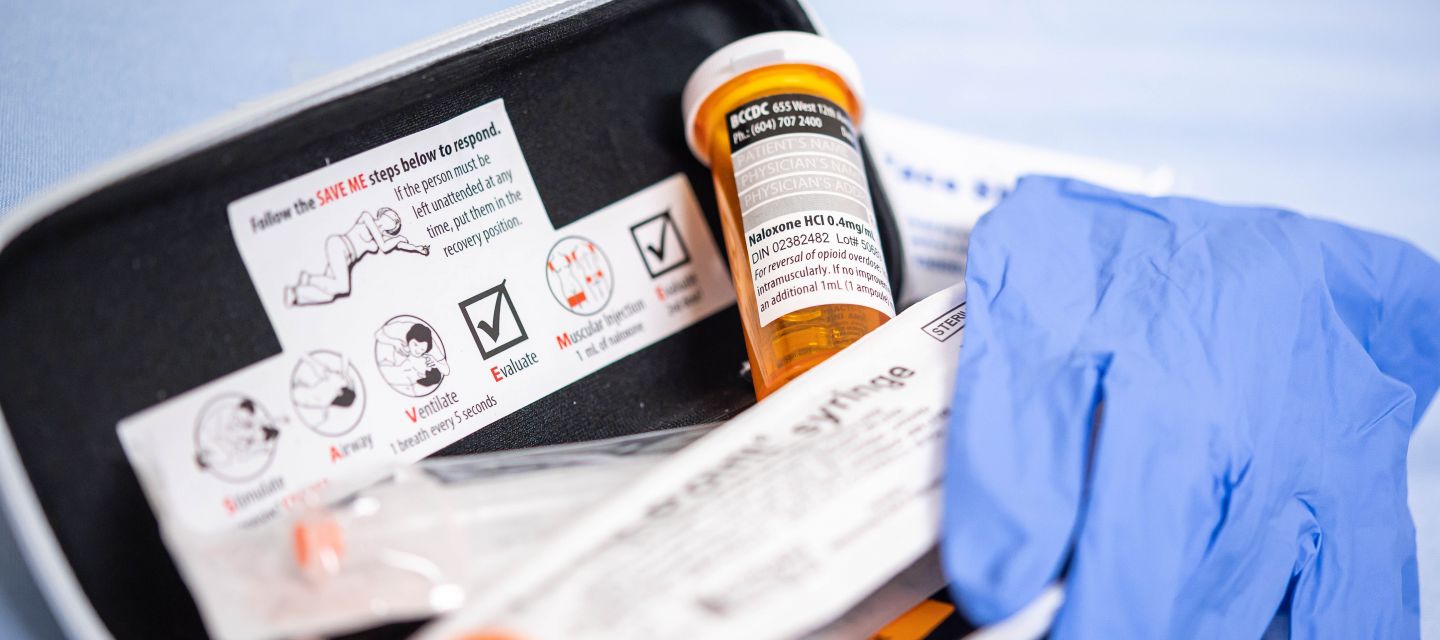

An important aspect of Buxton’s work is encouraging the use of respectful, non-stigmatizing language when describing substance use disorders, addiction and people who use drugs. Stigmatization has a direct impact on people who use drugs, she said. It contributes to isolation, which means people who use drugs may use alone and will be less likely to access harm-reduction services or treatment such as a supervised injection site or naloxone, a medication that quickly reverses the effects of an overdose.

Buxton’s work has played a significant role in reducing the number of deaths associated with illicit drug overdoses. She developed the drug overdose and alert partnership in 2011 and was instrumental in bringing take-home naloxone kits to B.C. in 2012.

Research carried out by Buxton and her colleague Michael Irvine found that, without access to harm reduction and treatment strategies such as take-home naloxone kits, the number of overdose deaths in this province would be 2.5 times as high. Since mid-2016, when the naloxone program ramped up in response to the growing overdose crisis, between 4,000 and 5,000 naloxone kits have been distributed every month.

“When you look at the data, especially the take-home naloxone program, there’s just huge numbers of kits that have been distributed,” said Irvine, a postdoctoral fellow at the BC Centre for Disease Control, Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions and Institute of Applied Mathematics at UBC, who led the research. “Without these interventions, there would have been many more deaths.”

Irvine said he often hears from colleagues in the United States, where the overdose crisis has also hit many communities hard, who are surprised by the “sheer number” of naloxone kits that have been distributed in B.C.

“They’re kind of blown away by it,” he said. “We really are ahead of the curve in B.C. in terms of harm-reduction strategies, despite the fact that we still see very high numbers of deaths.”

Improving access to care could make a difference

Dr. Seonaid Nolan sees the benefits of take-home naxolone kits in saving lives.

Nolan, who works as an addiction medicine physician at St. Paul’s Hospital, sees patients when they are at their most vulnerable. While she strives to help every patient she meets as best she can, Nolan believes more people could be helped if access to care was improved.

“Part of the reason why the response to the HIV crisis in the 1990s was so successful was that health-care providers essentially brought treatment to the patients,” she said. “There wasn’t an expectation that patients had to show up at a clinic.”

She believes the solution to the crisis lies in a similar approach with outreach teams staffed with peer workers and health-care providers finding patients in the community, and helping them navigate the health-care system to make access to care as low-barrier as possible. Reducing the stigma will also encourage more people who use alone to “come out of the shadows,” she added.

“The highest proportion of people who are dying from overdoses are individuals who use alone in their place of residence,” said Nolan. “That really signifies how addiction is such an isolating disease.”

‘We need to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach’

Experts agree the overdose crisis is a complex health and social problem that can’t be solved through one intervention alone. Lindsey Richardson, associate professor in the UBC department of sociology and a research scientist at the BC Centre on Substance Use, understands how complex the issue is.

Richardson led a study examining whether varying the timing and frequency of income assistance payments can mitigate drug-related harms linked to the existing once-monthly payment schedule. Fatal overdoses have been known to jump 35 to 40 per cent in the five days after monthly cheques are issued.

She and her colleagues found that, while changing how and when people who use drugs receive their income assistance payments could reduce escalations in drug use around cheque day, the changes could also have unintended consequences that increase individual drug-related harms. Based on their findings, she recommends that any changes to the income assistance system allow for individual choice about timing and frequency of payments.

“We need to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach,” she said. “There is no panacea that is going to solve this crisis for everyone because everyone’s substance use looks different.”

While it is encouraging to see new data showing a short-term slowing of the overdose crisis in B.C., Richardson said people are still dying at an unprecedented rate.

Richardson believes the crisis can be addressed successfully but only if it’s a community-led effort.

“This is the public health challenge of our time right now,” she said. “Everyone needs to do their part. It needs to be all hands on deck.”